ABOVE: LAURIE O’KEEFE

In the 16th century, when the study of human anatomy was still in its infancy, curious onlookers would gather in anatomical theaters to catch of a glimpse of public dissections of the dead. In the years since, scientists have carefully mapped the viscera, bones, muscles, nerves, and many other components of our bodies, such that a human corpse no longer holds that same sense of mystery that used to draw crowds.

New discoveries in gross anatomy—the study of bodily structures at the macroscopic level—are now rare, and their significance is often overblown, says Paul Neumann, a professor who specializes in the history of medicine and anatomical nomenclature at Dalhousie University. “The important discoveries about anatomy, I think, are now coming from studies of tissues and cells.”

Over the last decade, there have been a handful of discoveries that have helped overturn previous assumptions and revealed...

Here is a sampling of some of those discoveries.

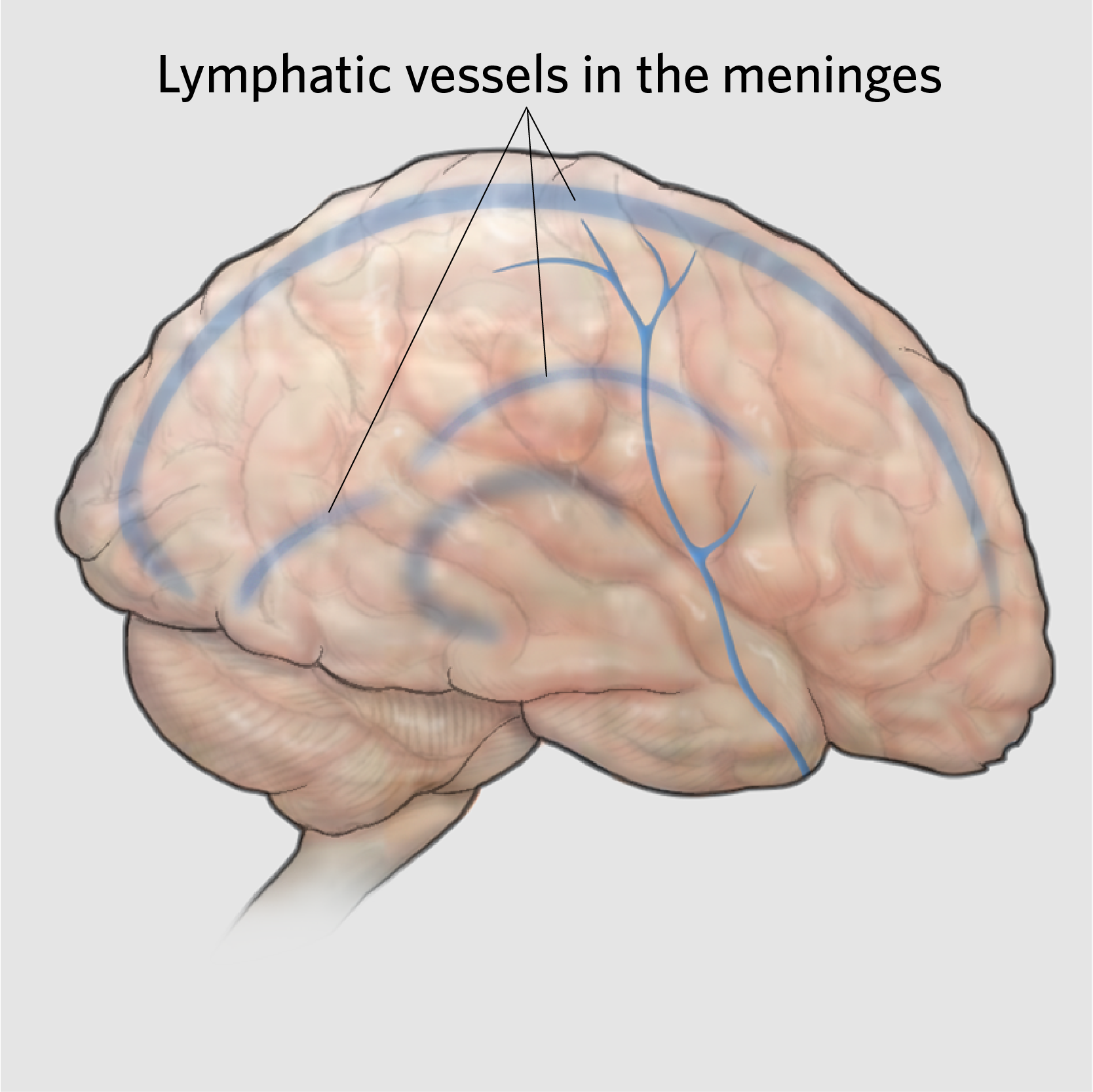

The brain’s drain

The lymphatic system, a body-wide network of vessels that drains fluids and removes waste from tissues and organs, was long-believed to be absent from the brain. Early reports of lymphatic vessels in the meninges, the membrane coating the brain, date as far back as the 18th century—but these findings were met with skepticism. Only recently has this view been overturned, after a 2015 report of lymphatic vessels in mouse meninges and the 2012 discovery of the so-called glymphatic system, an interconnected network of glial cells that facilitates the circulation of fluid throughout mouse brains. In 2017, neuroimaging work revealed evidence for such lymphatic vessels in human meninges.

Fluid-filled spaces

In 2018, researchers reported that the space between cells was a collagen-lined, fluid-filled network, which they dubbed the interstitium. They proposed that this finding, which emerged from close examinations of tissue from patients’ bile ducts, bladders, digestive tracts, and skin, may help scientists better understand how tumors spread through the body. The team also called the interstitium a newly-discovered organ, but many dismissed this claim. “Most biologists would be reticent to put the moniker of an ‘organ’ on microscopic uneven spaces between tissues that contain fluid,” Anirban Maitra, a pathologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Center, told The Scientist last year.

The mesentery: An organ?

Until recently, the prevailing view among scientists was that the mesentery, the large, fan-like sheet of tissue that holds our intestines in place, consisted of multiple fragments. In 2016, after examining the mesentery of both cadavers and patients undergoing surgery, a team of researchers concluded that the mesentery was actually a single unit. This wasn’t the first time the mesentery was described as continuous—in one of the first depictions of the structure, Leonardo da Vinci also portrayed it in this way. But in the 2016 paper, the scientists argued that its continuity should qualify the mesentery as an organ. As with the interstitium, however, other experts have objected to this claim. In both of these cases, “there seems to have been a misunderstanding of what the term organ means,” Neumann says.

Blood vessel networks in bone

In January 2019, scientists described a previously unknown web of capillaries that pass through the bones of mice. Textbooks describe large veins and arteries jutting out the ends of bones, but this newly-described network of tunnels provide a faster route for blood cells produced in the bone marrow to enter the circulation. The research team also looked at human bones using a variety of methods: taking photos from patients undergoing surgery, conducting MRI scans of a healthy leg, and investigating extracted samples under a microscope—and revealed a similar, albeit less extensive, system of capillaries.

Reptile-like muscles in fetuses

Last October, researchers reported that muscles typically seen in reptiles and other animals—but not people—were present in the limbs of human embryos. Using a combination of immunostaining, tissue clearing, and microscopy, the team generated high-resolution 3-D images of upper and lower limb muscles in tissue samples from preserved 8- to 14-week-old embryos and fetuses. These structures, which disappear before birth, may be anatomical remnants of our evolutionary ancestors that disappear during the early stages of development, the authors suggest. They only examined 13 images, however, so experts caution that it’s a preliminary finding that needs to be replicated in a larger sample.

The fabella makes a comeback

The fabella, a tiny bone located in a tendon behind the knee, is becoming more common in humans, according to a study published last spring. After reviewing 58 studies on fabella prevalence in 27 different countries, researchers reported that people were approximately 3.5 times more likely to have the little bone in 2018 than 1918. The cause of this trend remains an open question, but the authors suggest that changes in muscle mass and bone length—driven by increased diet quality in many parts of the world—could be one explanation.

Diana Kwon is a Berlin-based freelance journalist. Follow her on Twitter @DianaMKwon.

Interested in reading more?